This month, two independent cases of bird flu were detected in North American children without any known exposure to infected animals, raising concerns that the H5N1 virus that causes it is inching closer to evolving in a way that allows it to spread between humans.

Since April, 55 H5N1 cases have been reported in humans, and all but three have occurred in farmworkers in close contact with dairy cows or poultry, which the virus is infecting in droves. But health officials have not been able to determine the source of three cases in humans, raising questions about whether there is low-level community spread happening.

On Nov. 9, government officials in British Columbia reported that a teenager tested positive for H5N1 with no known exposure to an infected animal. Last week, a child in the Bay Area also tested positive for bird flu without any known exposures. These two cases follow a third infection in Missouri reported in September, for which health officials were unable to determine the origins of the infection after an extensive investigation.

“The big takeaway is that there is more community spread than is being detected,” said Dr. Abraar Karan, an infectious disease physician at Stanford University. “When you can’t figure out where the infection came from, that raises a lot of red flags.”

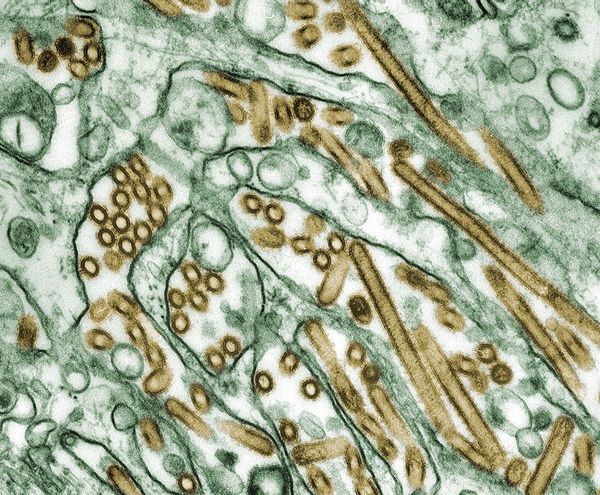

Colorized transmission electron micrograph of Avian influenza A H5N1 viruses (seen in gold) grown in MDCK cells (seen in green). (Smith Collection/Gado/Getty Images)Without exposure to farm animals, it’s possible these children could have become infected after coming into contact with a wild bird infected with the virus. Another possibility is that they could have come into contact with a domesticated animal that had the virus. However, in the Canadian teen's case, all of the pets they came into contact with tested negative, said Bonnie Henry, a public health officer for the province of British Columbia in Victoria, Canada, during a press conference.

Colorized transmission electron micrograph of Avian influenza A H5N1 viruses (seen in gold) grown in MDCK cells (seen in green). (Smith Collection/Gado/Getty Images)Without exposure to farm animals, it’s possible these children could have become infected after coming into contact with a wild bird infected with the virus. Another possibility is that they could have come into contact with a domesticated animal that had the virus. However, in the Canadian teen's case, all of the pets they came into contact with tested negative, said Bonnie Henry, a public health officer for the province of British Columbia in Victoria, Canada, during a press conference.

“There is a very real possibility that we may not ever determine the source,” Henry said.

In another press conference hosted today, Henry said the case in the teen was a “rare” event and that all of the healthcare workers or close contacts of the teenager have tested negative after a 10-day incubation period.

“Even if there was a mutation in the young person in the virus here, right now, that would have died off because we have not seen any other transmission,” Henry said. “That is reassuring, but it just reminds us that the influenza virus can change quite rapidly, so we need to be on our guard.”

"This virus seems to be increasing in the numbers and types of humans it is infecting."

While the H5N1 virus has not shown the ability to spread between humans, each time it infects someone or mammals like cows and pigs, it raises the chances that it could evolve to adapt in a way that makes it more transmissible between humans, possibly triggering a pandemic like COVID-19. This is of particular concern amid the standard influenza season because genes could swap and mutate in an organism infected with both the seasonal flu and bird flu in a process called viral reassortment.

“It is always difficult to know exactly what set of mutations are actually required to make [human-to-human transmission] happen,” Karan told Salon in a phone interview. “There are mutations that make the virus more effective at finding and entering cells; mutations that allow certain enzymes within the virus to more effectively replicate the virus and help it spread more; mutations that can help the virus be more stable in aerosols … Generally, you need multiple mutations to occur for you to have something that efficiently transmits between humans.”

Want more health and science stories in your inbox? Subscribe to Salon's weekly newsletter Lab Notes.

Again, if the H5N1 virus develops the ability to efficiently spread between humans, the world will be faced with another pandemic, said Jennifer Nuzzo, an epidemiologist and director of the Pandemic Center at Brown University School of Public Health.

“The overall trend is that this virus is really increasing its geographic distribution, the virus is really increasing the number of animal species it's infecting, and this virus seems to be increasing in the numbers and types of humans it is infecting,” Nuzzo told Salon in a phone interview.

The rate at which H5N1 is spreading in cows is unprecedented. As of this writing, roughly 600 dairy herds had been infected in 15 states, and more than 100 million poultry were impacted in 49 states, according to the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC). This week in California, bird flu was also detected in raw milk that was being sold in stores, another first. Though the risk level of contracting bird flu from drinking milk is unknown, it has been shown to transmit the virus to cats and other animals. The virus was also detected in pigs for the first time, which is particularly concerning because pigs are known as “mixing vessels,” as they can contract both human and avian pathogens, increasing the chances of viral reassortment.

In the 2009 swine flu pandemic, multiple reassortment events in pigs and birds led to the novel H1N1 virus strain, which led to 60 million cases and 12,000 deaths in the U.S. in its first year of circulating, per the CDC.

We need your help to stay independent

Although the majority of cases in humans have been mild, bird flu historically has a far higher case-fatality rate than the current outbreak. This is partly because most cases circulating before this outbreak were caused by a type of the virus that primarily affects birds, while most of the cases in the U.S. in the current outbreak have been caused by the type that primarily affects cows.

However, the Canadian teen was hospitalized in critical condition with a severe reaction to the virus. Viral genome sequences indicate the teen was infected with the type of bird flu typically found in birds, and that this type of the virus might have mutated in a way that increased its ability to attach to the human respiratory tract. However, the teen developed an eye infection first, followed by a lung infection, which could suggest that the virus adapted after it infected the young person.

“It’s consistent with the idea that the virus might have evolved within that individual,” says Hensley.

Cases like the one in Canada will likely be caught in surveillance systems due to their severity. While milder disease is obviously better for human health, it also makes it more challenging to detect community spread, said Dr. Erin Sorrell, a virologist at the Johns Hopkins Center for Health Security. In one CDC study, 7% of farmworkers had antibodies that suggested they had previously been infected with bird flu, which is far higher than the proportion of cases actually reported.

“Because it is presenting in a mild fashion and initially came out in a very vulnerable population that did not have access to care, the virus has been able to essentially sustain itself undetected,” Sorrell told Salon in a phone interview.

Meanwhile, the world is watching anxiously as the U.S. reacts to bird flu, and some have criticized the nation for not stamping out the virus in birds or cattle before it infects more humans. As of this writing, bird flu has been detected in more than 10,000 wild birds, which is concerning as many of these species continue to migrate to other parts of the world. Last week, bird flu was reported in Hawaii and continued to spread in other countries in Europe like the Netherlands.

“I am really concerned that the investigation by the USDA and the methods put in place to limit transmission are clearly not successful at this point,” said Dr. Michael Osterholm, an epidemiologist and director of the Center for Infectious Disease Research and Policy at the University of Minnesota. “This is a real challenge.”

Time will tell if the cases in Canada and California were “one-offs” like the case in Missouri. But with each additional human case that is not tied to farm animals, that seems to be becoming less likely.

“This virus continues to spread, popcorning up around the country and over the border in Canada, and I think this means this is going to be a protracted threat to U.S. agriculture and public health,” Nuzzo said. “The virus is not going away, we are not taking steps to make it go away, and therefore it is going to keep on going.”

Shares